As the neonatologist on call in the NICU, I go to meet the mother of a new preterm infant who’s struggling to survive on mechanical ventilation. I know the specifics of the case played a role in the infant being born at just 24 weeks old. Yet, while standing at the patient’s bedside, I cannot help but feel a deep sadness as I ponder the broader societal risk factors for this Black mother-infant pair. Due largely to the cumulative effects of structural racism, Black women deliver preterm more frequently than other women, and Black infants have more than twice the infant mortality rate of other racial groups. While these statistics might seem abstract to some, the sick, tiny infant in the isolette in front of me makes them all too salient.

Between racial disparities in COVID-19 outcomes and the national awakening to the impact of police brutality in the Black community, the concept of anti-racism is quickly gaining traction in areas where it’s been needed all along. Historian and race scholar Ibram X. Kendi’s book How to be an Anti-Racist is one of several books about racism currently topping bestseller lists. One of Kendi’s major premises is that people and institutions are either racist or anti-racist; there is no third option. In medicine, we have relied heavily on living in this space of a debunked “third option.” We’ve clung to the idea that a doctor’s job is to fight disease with a cool head and steady hands, not to fight systemic discrimination with a fiery activist spirit.

But racism is woven into the fabric of every facet of society, including medicine, and it self-perpetuates. Either the medical field works to become actively anti-racist, or we stay complicit and make it clear we’ve chosen the other option.

Our profession calls on us to “do no harm,” but it also sits in a place of inaction while societal abuse is being perpetrated.

My goal as a physician is to bring this national discussion about anti-racism into medical training and medical care. This is no small task. Like much of America, medicine resides in a paradox of knowing yet not acknowledging the racism Black Americans face. There is awareness among medical professionals that, on average, Black families live in more impoverished neighborhoods and are more likely to have public insurance. Through inaction and lack of acknowledgement, the medical field seems to accept the extreme disadvantage and generational trauma that Black Americans have endured throughout history — and which they continue to endure because of white supremacist ideology and racist American structures.

Owning up to complicity is difficult.

We have an abundance of research on racial disparities in health and healthcare. Studies tell us over and over that Black Americans disproportionately suffer chronic diseases that shorten life spans. Studies reveal that medical trainees believe Black people have thicker skin and are less sensitive to pain; studies thoroughly document the ways in which Black patients’ pain is misdiagnosed, mistreated and outright ignored.

And yet there have been minimal improvements since the 1990s in the disparities that affect the health of Black Americans. Our profession calls on us to “do no harm,” but it also sits in a place of inaction while societal abuse is being perpetrated. Inaction allows racial bias to seep into the exam room and undermine the care that Black patients receive. Inaction does harm.

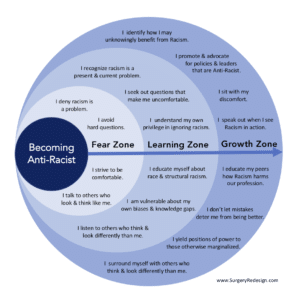

SurgeryRedesign.com recently published a graphic that shows the three main stages of becoming anti-racist: the fear zone, the learning zone and the growth zone. In my estimation, healthcare is in the late-fear, early-learning zone.

Most medical journals’ discussions of racial health inequities minimize racism as the source. Instead, poor health in minoritized communities is falsely attributed to “genetics” or “socioeconomic status.” Most people in medicine are still striving to keep conversations about race comfortable, and cannot fully acknowledge their privilege in the system. Most people cannot clearly identify the knowledge gaps that need to be filled to improve care. What would it take to move medicine into the growth zone?

To start, we need a revolution in how we train students in medicine, nursing and other health professions. We need to move beyond familiar implicit bias lectures and introduce a new curriculum, centered around a deep understanding of critical race theory, structural inequities, historical racism and violence, and modern-day manifestations of racism in healthcare. This will likely mean bringing new types of scholars into the walls of medical schools, including sociologists, anthropologists and other non-physician teachers.

A wonderful example of this new curriculum in practice is at the University of California, San Francisco, School of Medicine, which has partnered with UC Berkeley to develop the Program in Medical Education for the Urban Underserved, known as PRIME. As part of this program, medical students learn physiology and disease through the lens of historical racial inequities. PRIME graduates a new type of physician with an entirely different understanding of disease etiology and cures. For example, instead of attributing higher rates of severe hypertension among Black patients to genetics, a PRIME graduate would be more likely to assess and address underlying societal reasons for such outcomes, including the chronic stress of racism, living in food deserts without access to nutritious food, and low access to neighborhood green spaces for exercise.

At every level, the system is designed to exclude minoritized students from entering and succeeding in medicine.

Second, physicians and other healthcare workers must accept that we cannot improve minority health by practicing medicine in silos. Social determinants of health, or SDOH, have a massive effect on disease incidence and severity, as well as death. The medical community as a whole can no longer sit and wait for other factions of society to advocate for national policy change, local policy change and improved standards of living for minoritized Americans. This includes advocating for improved access to healthcare (universal health insurance), improved education and employment opportunities (narrowing the racial wealth gap), and improved housing and access to clean air and water. The health impact of racial segregation has been well studied, and it’s widely known that ZIP code is predictive of life span in many cities in the US. If physicians are for saving lives, then we must address these SDOH with the same vigor with which we prescribe investigational drugs or encourage enrollment in the latest clinical trial.

Third, local change can be very powerful, and it can change the lives of patients. Each clinic and hospital can begin to measure the outcomes of their patients, including hospitalizations, disease severity and deaths, through the lens of anti-racism. This entails breaking down data by racial demographics and other important variables, and comparing health outcomes by race, gender and age. Doing this will likely expose disparities and health inequity, by which point the health system must be ready to create and implement programs to reduce these disparities.

The New England Journal of Medicine recently highlighted such an effort: In 2017, Boston’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital created its Health Equity Committee and started measuring health outcomes by race. The committee explored disparities through the lens of bias and structural racism, instead of treating “race” as the risk factor. It found that Black patients with heart failure were more commonly admitted to the general medical team and not the cardiology medical team. At that point, the committee launched two projects to decrease this disparity and make sure all patients received the same excellent care.

Fourth, the medical workforce must be desegregated. As Dr. Rhea Boyd, a pediatrician and public health advocate, wrote in The Lancet in her powerful essay “The Case for Desegregation”:

Just as Black teachers were not simply “underrepresented” in Ruby Bridges’ elementary school, nonwhite professionals are not simply “underrepresented” in the US healthcare industry. They are largely excluded, and when included, it is within systems that disadvantage and discriminate against nonwhites.

Starting at a young age, minorities, specifically Black Americans, are effectively excluded from entering the medical profession at multiple levels. Minoritized children have less access to high quality early education because of disparities in school funding. As a result, they’re less competitive for the Ivy league and other upper-echelon colleges, the feeders of most US medical schools. Without family wealth, many minoritized students cannot afford to attend medical school. We have data to show that the vast majority of medical students in this country are from the highest income brackets, which are almost exclusively white. In this way, the pool of physicians in no way matches the American population.

In medical school, Black and minority students are evaluated less favorably by supervisors, and data shows that important markers of achievement, like admission to the medical honors society and letters of recommendation, are biased in favor of white students. At every level, the system is designed to exclude minoritized students from entering and succeeding in medicine. To be anti-racist, medicine must acknowledge and change these barriers.

There are multiple ways in which the current medical system is not supporting minoritized medical students and physicians, and there are multiple ways that the system is failing minoritized patients. We have the anti-racism tools needed to correct these problems. The question remains: Does the medical field have the bravery and the will to implement anti-racist practices to measurably improve the system? We can step up or we can stay complicit. There’s no third option.

This article has been updated.

WOW!!!!! Bravo!!

We need action and support from the top. Starting first with the medical leaders. Action Is Real !!

THANK YOU!

That’s a nice thought but realistically there are always gonna be people of diverse backgrounds and there will always be racism

Correct, but it doesn’t mean the fighting should stop. We’ve been complicit and patient for too long. It’s not a sprint, it’s a marathon.

Life is pain, suffering and fight. I understand the frustration because we’ve been doing it for so long people just want to be happy, but turning your back isn’t the solution. We need to learn to have balance.

We spend so much intellect, time, money and countless other resources on technology and business, and improving them… constantly problem solving and optimizing, but when it comes to people, especially minorities, we become complicit.

How can we evolve into better human beings, when we aren’t motivated to change and we’re constantly complicit?

Thanks for writing this. I had the depressing impression these issues were still not getting any attention.

Can I get a bigger copy of the circle graphic?

I would like to read it

Sure! Here’s the high-res pdf (the article links out to it too): https://umich.app.box.com/s/d1zl3r2dlso7gs76wjfybv9z52m397ho

This is brilliantly stated! Thank you!!!!

Thank you for that well thought out piece. As a person of color I have experienced indifference due to racism in the medical field, although I am college educated women with excellent healthcare benefit. I was told that because I am black I have high blood pressure, even though I had prior issue. It turned out I had SLE, I was misdiagnosed and went into renal failure 15 years ago. And even then the bias continues because now it’s assumed I had kidney failure because I have diabetes. Further incident, I was classified as obese,eventhough I went to four specialist admitted to the hospital begging for someone to help me because I kept swelling and all they said was to lose weight. It turns out that I had 90 lbs of fluid. Unfortunately as people of color you have to be your own advocate or else people die because of racist medical doctors. I know many friends and family who have had similar experiences.

Well written, bright minds are often wasted by lack of opportunities available to minority communities.

Excellent

Debunked third option? Not that I’ve heard… Maybe in some limited circles in society…

As far as the ‘indifference due to racism’, trust me, white people suffer from the exact same issues. The internet is filled with similar stories. You really need to advocate for yourself. Not everything bad is attributed to racism.

If you plan to refer to an author and his book, please get the spelling right! The author you are trying to refer to is Ibram X. Kendi. I’m sure he would appreciate the correction.

Excellent insight! The next horizon of anti-racist structures are medical device companies that design, develop and manufacture wireless and cloud-encrypted remote monitoring products that are safe and effective, yet unavailable to black and brown communities without access to the internet. We can do better!

I didn’t get “it” until Nessa Walsh related her story. An MD telling a patient their BP is high because they are black seems very silly. Although, I have been told that my high cholesterol could be hereditary.

As a firefighter EMT, I don’t judge patients by race. I treat everyone with care, respect and kindness. As a human, I judge people by their actions and behavior, and how they interact with me. Race is absolutely irrelevant.

Note- black is a verb, Black is not a noun-as written by the author. In my opinion, a step toward ending racism is to not make blatant distinctions or hyphenate. If one is a citizen of the US, you are an American, a part of the team! It’s nice to have pride of heritage, but identifying as something other than an American, nothing more, nothing less, gives the impression of non allegiance. ( that’s my opinion)

As a student nurse 30 years ago, I was told “ darker people have thicker skin” when it came time to learn how to start IVs. I still have that phrase in my head but I know better that it is not true. How absurd those words were but they were formed by racist ideologies that still persist today in medicine. I think it’s about time we start tearing down and rebuilding the healthcare education system to teach future generations how to think more diversely, be anti-racist and make medical school more affordable for everyone in order to offer better care to our communities. We need to change the system and the words spoken within them.

We can’t stop racism, but all races need to be treated fairly, and be given opportunities to have the knowledge we need to have healthy mothers and babies..I am educated with a masters in education and yet I often find myself changing doctors, because I too want to be in control of my health, I want preventive plans, not just meds…I want my intelligence to be respected, as we work together to improve my health conditions…I am a Africa American woman, who is tired of being put in a limited group…